Energy efficiency and “sobriété énergetique” have to go hand in hand for a decarbonized Europe. Only combined they will help us significantly reduce our primary and final energy consumption, as well as the use of other resources – and hence diminish our impact on the environment.

The French are known and renowned in the entire world for producing great stuff: wine, cheese, art and sometimes, extraordinary concepts. In the realm of energy, it is precisely in France where the term “sobriété énergetique” has been coined and even inscribed in the national law – the law of energy transition for green growth from August 2015[1].

That’s a tough one to translate to other language as a literal translation might suggest something related to abstinence (relevant to wine, impossible when it comes to power and heat), while the concept itself hints more at our ability to apply the principles of moderation and frugality to the use of energy in everyday life.

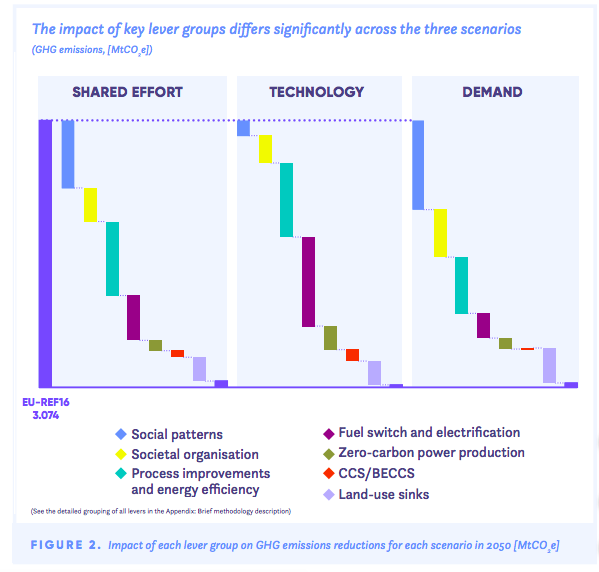

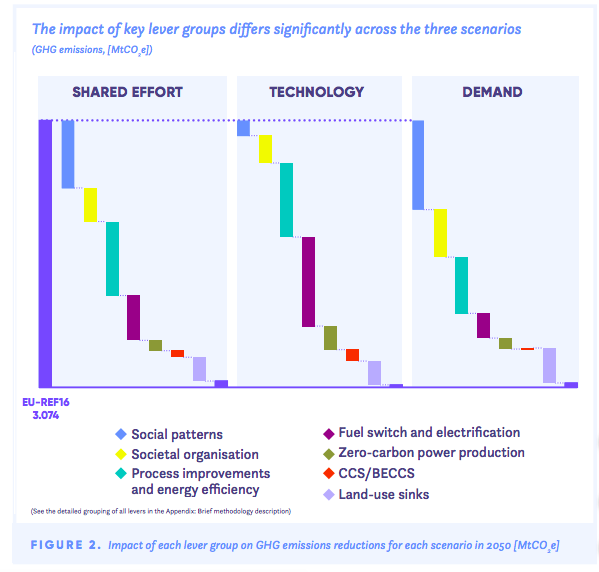

Why should we be assessing the opportunity to generalise this French concept to the rest of Europe? Mainly because we are at a very peculiar moment when it comes to the EU policy making: the European Commission is currently working on its 2050 low carbon strategy, which is intended to help integrate the COP21 (Paris agreement) commitments into its general regulatory framework. To do so, the Commission is widely consulting stakeholders to get their input and better conceptualise potential paths. And while the attention of stakeholders is mostly turned towards the most significant technology and process-related changes that need to be introduced and follow through to deliver on net zero carbon emissions at a 2050 horizon, relatively little is being said on what importance the “sobriété énergétique” would have to take us towards this carbon neutral and bright future. This propensity to focus on the former is reflected in the current EU framework, in particular the revised Energy Efficiency Directive and Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, where the “usage” bit is painfully missing. This is all the more jarring as the EED itself failed to setup targets ambitious enough, and expressed both in primary and final energy consumption, to drive necessary changes in the EU energy demand and consumption.

So what really is “sobriété énergétique”? First of all, it is not the same as energy efficiency, which can be defined as a measure or process that consists of reducing energy consumption by a piece of equipment with better efficiency and fewer losses in energy production or consumption. Hence, it is essentially about the performance and the proper use of various types of equipment and infrastructure with which we consume energy. “Sobriété énergetique”, or energy frugality for lack of a better term, aims at reducing our energy consumption not only by privileging more efficient equipment, but also by deliberately choosing to modify our usages of it, in order to reduce our overall energy consumption. “Sobriété” comes from a Greek word “Sophrosyne”[2] and refers to a conscious strategy to achieve moderation regarding our energy consumption, and to rediscover healthy limits (as opposed to overconsumption). To give an example it is about choosing well and sufficiently dimensioned equipment for our needs (fridge, flat we live in, car we drive or carpool); to supervise the way we use the equipment (level and duration of the use, for instance by avoiding standby mode), to cooperate and share through collective organisation (of transport means, housing, equipment and preference for short circuits of production and distribution, etc). Because it is centrally focused on consumers’ behaviour, it affects individual behavioural, wider consumption patterns and collective choices (including construction or expansion of heavy infrastructures). It is also about decoupling the notion of energy use from the service this usage provides and then making an educated choice of the most essential services – over less important, futile and sometimes even harmful usages.

As an example of how this principle applies and operates in real life in the building sector is for instance is when new districts are built and efficient and district heating networks are being chosen to deliver heat and sanitary water (and sometimes electricity if cogeneration units are installed). This is not only a technical and efficiency related choice – by opting for district energy, inhabitants of those “eco-quartiers” are also giving up on their freedom of choice and autonomy individual heating solutions provide them with, but with the view of greater collective benefits, including the possibility of massively integrate renewable and waste energy sources that are to be found locally, and reduced CO2 and fine particles emissions. The same applies when energy performance contracting and thermal renovation of buildings are being deployed, as part of deep staged renovation strategies. Both EPC and renovation works will surpass expected results in terms of energy savings and hence more rapidly yield the rate of return on investments, if buildings users are made aware of how their behavior can affect optimised and renovated installations. Overall, approaching energy transition from the territorial and district perspective is also a conscious choice and a change in our thinking and behaviour about energy production and that is likely to generate considerable positive externalities.

“Sobriété” is a significant piece of the decarbonization puzzle, because at its stands, the level of both carbon pricing, ambition of the EED revision, and achievement of the energy transition to local loops, is far from being sufficient to help reduce CO2 emissions enough to reach zero net carbon emissions by 2050. Responsible energy consumption is necessary to reduce overall primary and final energy use according to the scenario elaborated by the French think thank négaWatt[3], showing that “sobriété énergetique” represents half of the potential to reach 50% reduction of energy consumption in France. and behaviour about energy production and that is likely to generate considerable positive externalities.

Source: NET ZERO BY 2050: ZERO EMISSIONS PATHWAYS TO THE EUROPE WE WANT

“Sobriété” is a significant piece of the decarbonisation puzzle, because at its stands, the level of both carbon pricing, ambition of the EED revision, and achievement of the energy transition to local loops, is far from being sufficient to help reduce CO2 emissions enough to reach zero net carbon emissions by 2050. Responsible energy consumption is necessary to reduce overall primary and final energy use according to the scenario elaborated by the French think thank négaWatt[4], showing that “sobriété énergetique” represents half of the potential to reach 50% reduction of energy consumption in France.

“Sobriété énergetique” is not a revolution – it is a natural evolution of the concept of energy efficiency that might require changes in our individual behaviours and serious questioning of some of our habits. Its implementation might result in fostering better social interactions, based on solidarity and recognition of the value provided by sharing of goods and services. It might help change our social modal, fully inscribed it in the logic of circular economy and local energy planification.

Hence, in addition to reinforcing traditional drivers of transition towards low carbon economy, such as development of renewable energies, investment in energy efficiency across all economic sectors, and the use of carbon pricing based on polluter pays foundations, Europe should put greater focus on the principle of “sobriété énergetique”. How to get there is of course a big question mark. Because it touches upon almost all of the areas of our existence, the EU low-carbon strategy is precisely a great opportunity to incorporate this notion into the EU framework, along with the notions of energy efficiency first, and circular economy, directed towards increasing our awareness and providing us with tools to change our relationship with energy use, services its provides and to natural resources in general.

[1] In “La loi de transition énergétique pour une croissance verte (LTECV)”, the first title updates the country’s energy policy, where the notions of energy efficiency, energy security, maintaining of competitive energy prices, fight against fuel poverty, and “sobriété énergétique” are enumerated as its new principles.

[2] An ancient Greek concept of an ideal of excellence of character and soundness of mind, which when combined in one well-balanced individual leads to other qualities, such as temperance, moderation, prudence, purity, decorum and self-control.

[3] See http://www.ddline.fr/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/1601_Fil-dargent_Qu-est-ce-que-la-sobriete.pdf

[4] See http://www.ddline.fr/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/1601_Fil-dargent_Qu-est-ce-que-la-sobriete.pdf